In-depth conversation about the brilliance of the NS/Stick, its incredible versatility and unmatched tone

Exclusive interview with FBPO’s Jon Liebman

October 31, 2016

Originally a bass guitar player, Don Schiff is widely known for his master of the Chapman “Stick” bass. A native of Wilmington, Delaware, Schiff relocated to Las Vegas after high school, where he performed with the likes of Elvis Presley, Ann Margaret, Tina Turner, Peggy Lee, Sammy Davis, Jr and many others.

Upon discovering the Stick, Schiff’s musical life was forever changed. Having become well-versed on the instrument, Don moved to Los Angeles in the ‘70s, where he became an in-demand Stick player for live dates and recording sessions. His resume also includes having collaborated and/or recorded with a long list of music icons, including Elvin Bishop, Pat Benatar, Nia Peeples, Pam Tillis, Perry Como, Sheryl Crow, Dwight Yoakam, Eddie Money, Herbie Hancock, Shirley MacLaine and Ben Vereen.

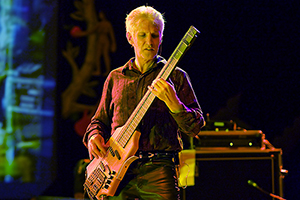

Don is a founding member of the Rocket Scientists, a progressive rock band, with keyboardist Erik Norlander and guitarist/vocalist Mark McCrite. His main instrument is the NS/Stick, co-developed by master instrument makers Ned Steinberger and Emmett Chapman.

FBPO: Before you were a Stick player, you were a bass player. Tell me about that part of your career.

DS: Around the time I was graduating high school, I got an interesting call to play [in Las Vegas] for Roslyn Kind, who is Barbra Streisand’s half-sister. I lived in Delaware and she was out of New York. My dad said, “Well, you’re out of high school and I know you want to go to Los Angeles, but hey, it’s a gig. Take it!” So I figured, okay, I’ll do that.

I went to Vegas. I was a bass player, 4-strings – they didn’t have 5-strings out yet. I did that at the Flamingo Hotel. It was a great experience. I think the gig lasted three weeks. I was out of high school, first gig, and I thought this is great! Life is fantastic. So I asked her manager for my next gig because they were going to go back to New York and I didn’t want to go back east; I wanted to stay out west. He said, “Okay, meet me in this hotel in the lobby tomorrow and I’ll tell you where your gig is.” And I thought, “Life is fantastic. How do you refuse that?”

So I get up the next day and I meet him in the lobby and he says, “All right. I got you a gig. You’re a busboy at this very hotel!” And I went, “Wow, showroom to busboy. Nice.” And he explained that you have to join the union in Las Vegas to play on the strip, [but] they don’t want you to do that; they don’t want any more musicians there. At that time, it was the highest-paying union, so everybody wanted to be there and they just wanted to discourage everybody, so you weren’t able to work as a musician in Las Vegas for six months. You had to do something else. So he said, “Now you’re a busboy.” On top of that, there was no guarantee that you were going to work because at that time, there were only twelve hotels. I thought, well the odds aren’t with me, but I’m in. I’ll do it.

FBPO: What were those next few months like?

DS: You had to sign in every week at the union, so I did. I was looking for an out, so at the union I was talking to the rep and he said the only out is if you can get a hotel musical director/contractor saying the need you specifically. Then all that is waived and you get your union card and you can work in the hotels.

Along came the fifth month. I was busing tables and there was somebody that befriended me that was a horn player and he kept telling the musical directors, “You know, I got this kid that plays great bass” and they seemed to be having a problem with the bass player, so he wore them out, I’m sure, for five months until they finally said, “Go get your busboy.” They came down the back kitchens and found me doing my job and said, “Go get your bass. After that, don’t bother changing; keep your smelly uniform on and take your bass over there and show them what you can do.”

So that’s how I got my start in Las Vegas. Then, through that, I got hired into the bigger hotel, the Hilton, which had Elvis and Tina Turner and Ann Margaret, all the really big acts, and so I got to play for them. I was able to build up a lifetime’s worth of resume in people you play with in a matter of a couple years. My trick for notoriety was, “Okay, I can read the music and anything that they write. I got it covered, however, I think I have something better. And so I would always play what I thought was a better bass line than what was written. I remember one time in particular, it was for the artist Ann Margaret, and it was an unbelievable chart, four and five sharp keys, and I thought, “This is incredible,” and it changes all the time. A lot of reading.” But I thought, “You know, I’m just going to play what I think.” At that time, she was doing Tommy, so I got to play some of the Who tunes that were orchestrated for large orchestra.

FBPO: Were any of those lines influenced by John Entwistle?

DS: They would have that. It was “Pinball Wizard,” so I had to play any kind of line that would be a signature line. There was an act that came through that was doing Jesus Christ Superstar and an example of that was the bass line while, in the play, Jesus is just being whipped with 40 lashes. The bass line, that was a classic was (sings) bum-bum, bum-ba-bum bum and I thought, “I’m going to play that 40 times? I don’t think so!” I would just elaborate on it to really make it a cool groove. I would do that with any signature bass line that came through. My reasoning being when the act went anywhere else or when the relief orchestra would come in for my day off, all the other bass players would play (what was written) and they were used to that. But what I did was give a lift, give it a little influence, a little more drive and then the acts would turn around, in this case, Ann Margaret, saying, “Wow, where did my groove go? What happened? What’s different?” So then I would be asked to go on tour with all the acts that I played for because they liked what was happening. It was fresh, it was a great drive and so I got known for that.

And then I had a great arrangement with the hotel because they didn’t want me to leave as their house bass player. They said, “We’ll make you a deal: If you promise, after you go on tour with whoever asks you to go on tour” – which many did – they said, “We’ll just keep your paycheck rolling, whether you’re working or not. Just promise that you’ll come back at the end of the tour.” So I had a great setup for a couple years there.

FBPO: How did you find out about the Stick?

DS: While I was in Vegas, they used to call them “Kicks” bands and they were just like a group of musicians that played on the strip that said, “Hey, let’s get together at my house and have a jam session.” So I did. Les DeMerle was the drummer; he was playing with Harry James at that time. We’re jamming away and he goes, “Hey, Don. I just came from LA and I was playing with a guy who plays bass and guitar at the same time. His name’s Emmett Chapman and he plays this thing called the Stick.

It resonated in me because I felt that, as a bass player, and I would think about it as a kid and dream of one day something, somewhere happening that would give me some notoriety. I felt that there would be something that would come along that would change a direction in my music for me. And so I called up Stick Enterprises and asked about it and he explained it a little bit to me. What’s funny, I was a kid, 19, 20 years old, never thought to buy paper and pencil, never really had anything to write them and ask Stick Enterprises about the instrument. I had a bag and I tore the bag up and used that as paper and wrote on it and sent it to them. And they still have that bag to this day at Stick Enterprises!

He [Emmett] invited me to come up. So I drove from Vegas to Los Angeles, saw it [and] bought it on the spot. I was so inspired by it. When I was watching it being played, I thought, “Oh, I get it. Just put it in my hands. Let me rip on it.” So I put it on and I was so disappointed, because the bass was in fifths and I’m used to fourths and it was inverted, so I kind of, in my mind, fell flat on my face, thinking I can’t say what I want to say on the bass; it was all backwards. All in all, it took about three months of me thinking, “Did I waste my money?” And back then, it was 350 whopping dollars! It would be great if they were $350 now! After three months, I got the hang of it and I thought what an incredible and ingenious idea a bass in inverted fifths was. And of course the melody side is in fourths, which I could easily understand.

FBPO: That must have changed your whole approach to making music. The Stick is so much more versatile than a traditional bass. Talk a little bit about some of the different techniques you can apply to the Stick.

DS: The Grand Stick is six and six; the standard Stick is five and five. You’re just getting an additional string on each side. People say, “Which is better?” Neither one is really better. It’s just that you have the extra string. You just move your finger over a little more and you’ve expanded your arrangement range, but the “meat and potatoes” is the five and five.

FBPO: Explain the string configuration.

DS: For the regular, there are five melody, five bass. All the low notes are in the center of the instrument and go higher toward the edge on either side. So your melody is straight fourths and your bass is in fifths, going from the middle toward the edge, in the opposite direction. The reasoning behind that is that when the bass is in fifths, it goes higher much fast than in fourths, so you can now hit a bass note and, with your same hand, reach your fingers over and form a chord, all on the bass side. It doesn’t sound like a bass chord, which is very, very big, not melodious. It’s thick. And so (with) this, you’re getting that low, great bass note and you’re getting a very melodic chord in one hand. Now you still have a whole other hand to play on the other side of the Stick to do your melodies, to fill out the arrangement of the chord, make it a polychord, do whatever you would want.

All of the sudden, as I envisioned it in my head, it’s the piano of bass and guitar. You have two hands playing separate parts. You can play dual chords, you can keep a bass line and a melody going. [You can] comp chords in one hand and [play] a melody [in the other], all just by tapping.

On the Stick itself, there isn’t a lot of room to do any plucking. There’s really not a whole lot of room to dig your fingers in, but you can do it. It also has a very, very beautiful, distinct sound. The bass sound of the Stick is a great bass tone, unique to itself.

The challenge for me back then was (that) bass lines, classic bass lines, are all in fourths. They have a feel that lays perfectly in fourths, not in fifths. So when I would do sessions, time is money and rarely was there, “Oh, we don’t mind. We have time to experiment.” It wasn’t that; it was, “Hey, don’t bring in this weird instrument and start experimenting on our dime. We’re calling you because you’re a bass player. Play bass!”

I would never tell them it was a Stick or anything new. I would just come in with this strange instrument and I purposely adapted an ability to make my fifths tuning have bass lines lay like they were in fourths. It takes a little bit (of work). It’s give and take.

On the other hand, playing bass in fifths greatly expanded my view of how a bass line can lay. Then I did the opposite when I would pick up my bass. I would play fifths bass lines and make them lay and sound appropriate on my fourths bass. It was such a mind-expanding experience to have the Stick and really broaden my musical horizons in writing and arranging.

FBPO: I guess Red Mitchell figured that out before everybody else!

DS: Yeah!

FBPO: What about, specifically, the “NS” Stick? How does that differ from other Emmett Chapman and other Ned Steinberger instruments?

DS: Great question, Jon! Then the NS Stick came along in ’99, I believe as a prototype, and we all got a chance to play on it a little bit and give opinions. Stick Enterprises said, “Don, you take it for a year and let us know what it does, what your thoughts on it (are). So I did and it was primarily a tap instrument, but it has the ability and the spacing so you can pluck it like a bass, strum it like a guitar and also tap it like a Stick.

So for me, all of the sudden, on a session or on tour, I didn’t have to take a Stick and a bass. I thought, “Wow, this gets an unbelievably great Stick tone, I still have that.” It is one of the finest bass tones I’ve ever recorded with. I describe it as right out of the jack. Plug it into an amp, plug it into any recording session and it sounds like the finished master bass tone. It is huge! You can play that tone. Engineers would flip over it. They’d say, “Whenever you come to a session for us, you bring that particular Stick, an NS, which was a prototype. I was ready to get one of the first ones off the line and the producers and engineers would say, “Get whatever NS they want you to have, but when you show up for a session, you show up with that one because that is a phenomenal tone.”

And they would put it on the teeniest, tiniest speakers that they had in the studio and they said, “Watch what happens. We’re going to undermix your bass.” And they would play it on the tiniest speakers and it was still pokin’ through strong. You could still feel it. And then when they put it up on the huge speakers, even undermixed, it was such a pure bass tone and so beautiful in its sonic range. It just always cut through. There weren’t things you had to do any subtractive mixing with, nothing you needed to add; it was just all there, really refined.

FBPO: How many strings does it have?

DS: It has 8, split in 4 and 4, which gives you the illusion of, “Okay, I’ve got four bass strings and I’ve got four melody strings.” They all run in straight fourths. I primarily look at the instrument as an 8-string “Super Bass.” [That’s] what it got termed in a lot of studios that I would go into. They would say, “Bring that Super Bass!”

FBPO: How is it tuned?

DS: B-E-A-D G-C-F-Bb. They also ship them with a parallel guitar tuning, so that would be B-E-A-D G-C-E-B, so you can still form your guitar chords if you’re familiar with that. It is almost a fourth lower in pitch (than a guitar) when you go to the highest note on the NS. I tune it (in) straight fourths for the simple reason that I could play a bass note with my first finger and with my same finger – it looks like a bar chord on a guitar, a major chord – I can form and play a bass line in one hand and still retain a chord with that same hand so I can pluck and strum at the same time to get the plucked bass tone.

I don’t always have to have a tapped tone, which is wonderful, but no one tone fits every situation. Sometimes I want that tap, that clear, very percussive sound; sometimes I want that warm P-bass sound and so I had options. And the beauty of the instrument, too, is I can switch that technique within a song and have it be equal. It doesn’t sound like,” Oh, the tone dropped; now you’re tapping” or “Now it’s overly loud because you’re plucking the string.”

It’s very seamless throughout the whole instrument, so that was a great discovery for me. If you tap, of course, you can play a bass note and a chord at the same time. If you’re plucking and forming a chord in one hand, you pluck the bass and you would strum the chord. But I figured out if I slapped the bass note, tap it with my thumb and then point my first finger from a curled position, I am strumming the melody strings and plucking the bass at the same time, so it just opened up all worlds for me.

FBPO: What about the Rocket Scientists? Would you say your Stick playing is an important component of the band’s sound?

DS: Oh, yes. It definitely is, especially with the advent of the NS Stick because then we were back to having whatever we wanted. Erik Norlander is an incredible engineer. He was able to get what I thought (was) one of the greatest Rickenbacker sounds, because it is progressive rock and it has a sound to it, as well as the Stick tone that Tony Levin stylized. It also had a great bass tone in itself. With a little smart EQ-ing, we were able to get some of the greatest Rickenbacker tones, I thought, some of the greatest P-bass tones.

The pickups on the NS are EMGs, full range, so everything is there, the ability to “chameleon” the sound is just notching the tones out that you wouldn’t want. Everything is there, pure and equal, a brilliant tone all on its own. That’s always my first choice in a session. If they aren’t sure of the tone they want, I just pull out the NS and start there. It doesn’t always make it. Sometimes I have to bring my Rickenbacker or my Precision bass because those are very stylized, depending on what somebody would want.

FBPO: I notice that sometimes you hold and play it like a regular bass. It must be nice to have that option too.

DS: Yeah, I love that! It is glorious. You don’t always have to play the highest strings. The other component that makes it different from, say a 7-string or an 8-string bass is Emmett’s incredible thought process of having the low B – I believe it’s a 128, which is standard. It has a special core to it to facilitate a full-range tap tone and it plucks just as well as a standard bass. But the strings go thinner in gauges a lot faster than a bass would, a 7- or 8-string bass. And the beauty of that is when you get really, really high up on the strings, they become very melodic and not very thunderous in tone, up high, and they don’t get that choked, thick note when you play way, way, way high up on the neck. And so, you’ve got the beautiful low bass, supported by these beautiful melodic higher strings. That’s one of my favorite things.

FBPO: What’s keeping you busy these days?

DS: Well, I moved to Napa and put a studio in the first floor. I opened that up in March and realized that I’m only six and-a-half hours up the street from where I was in Los Angeles. Occasionally I need to go back, but mostly, all of my sessions were over the Internet. Threre’s a wonderful guitarist named Phil Brown out of Nashville. I’ve known him for 40 years. He’s doing an album and he said, “I want you to play on it.” And I said, “Okay, I’ve got the studio ready to go.” So I would look at him on my phone and he would hear what I was doing through my studio and I thought, “I guess I was born in The Flintstones recording age and now I’m in The Jetsons recording age,” seeing people and they can hear what I’m doing and he could hear the full range of my bass, which I was very, very surprised with because I was being my own police monitor of, “Okay, wait a minute. Did you hear that maybe that note wasn’t as clean as it could be?” and he would immediately stop and say, “No, no, no, no, let’s go back and get” you know, “bar 16” and it was incredible.

So here I am recording an album in Nashville while I’m in Napa and then I got a call from a wonderful producer, Andy Kinch, who had one of the lead singers in the Electric Light Orchestra (Kelly Groucutt). He passed away, God rest his soul. He had recorded a tune for Andy and Andy said, “I’ve got his vocal and I’m trying to arrange it. I’m here in London. Will you play on it?” So we did it the same way. There I was in London and in Nashville, all in the same month, recording tracks for people. And it’s just wonderful. You get paid through PayPal, you see them on your phone and record away.

FBPO: How about the future, Don? What else would you like to do that you haven’t already accomplished?

DS: Well, that’s a great question. I’ve always been a session musician or a touring musician, so I always put everybody else’s music first, before mine, and I don’t have that many albums out. So, for the future, there are so many things I want to say, musically, beyond just Stick music. I’ve co-written songs for different artists. I have a gold album with Pat Benatar that Tully Winfield and I wrote for, so, that’s not just Stick; it’s arranging. I bought a cello, a viola and a violin because I want live strings on my sessions, and so I’ve been constantly learning new instruments, new ways to record and so I just want to keep expanding my horizons, musically, and pushing the Stick to its limit as well.

Every time I see Emmett, God bless him, he just celebrated his 80th birthday. We had a wonderful celebration and his daughter asked me to play a song for him. And I though okay, let me make this special. So I came up with a new technique on the NS where I can tap a bass note, form a chord in my right hand and I played the Louie Armstrong song, “It’s A Wonderful World.” I played it for Emmett and the technique was, in my right hand, I’m playing octave Wes Montgomery style. After I hit the melody note, I then pluck it so I’m hitting the strings that my left hand is forming the chord with, so I’m hitting a bass note on one, melody, pull-off, so the left hand is sounding like bass/chord/bass/chord, comping back and forth, while I’m doing Wes Montgomery-style octaves in my right hand and it was a new technique and I figured, “Emmett, for your birthday, I’m going to show you this and I was asking him about it later and he goes, “You know, I always describe your hands as you’re doing two techniques in one hand, so it’s like you have four hands going at the same time. I can’t really see it when you’re doing it, but, anyway, we celebrated his 80th birthday that way.

FBPO: What would you be if you weren’t a bass player?

DS: Very scary to think. Of course, as a musician, you don’t always have that solid career coming in. I’ve done many, many things. If I wasn’t going to be a musician, out of high school, thinking maybe I wouldn’t have a music career. I think in the 11th grade, I was going to be a mortician. My reasoning was I was very shy, it would be quiet, there’s nobody looking over my shoulder. So I went to a mortician’s place and he walked me thought it and I went, “Wait, there’s also a lot of college and a lot of studying.” I really did not enjoy school. I wasn’t a horrible student, but it wasn’t a great experience for me. I was contacted by the University of Delaware that if I told them I would join their jazz band that I would get a scholarship, but I thought I don’t want to learn how to play, I need the experience of playing. I already have inside of me the burning desire to say what I want to say musically and I just thought you can’t teach that in college. I needed to play. They can talk about music all you want. There’s doctorates in music and they can talk the language brilliantly, but I’m a player.

For more information about the NS/Stick and other models, visit the Stick Enterprises website.