Classically trained cellist finally expresses his lifelong love for the bass

Exclusive interview with FBPO’s Jon Liebman

July 13, 2020

Photo by Jamin Dion Smith

Growing up in Winter Haven, Florida, Derek Menchan’s love for the bass began at an early age. As enamored as he was with the bass, though, he was told his hands were too small to play it and was encouraged to take up the cello, which he studied seriously all the way through his college years. As a performing artist, Menchan has played in a wide variety of musical genres, having shared the stage with pop and rock icons Ray Charles, Diana Ross, Rod Stewart, Stevie Wonder, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, conductors Leonard Slatkin and Kurt Masur, and cellists Janos Starker and Mstislav Rostropovich. Derek has been a soloist for numerous world class orchestras and ensembles and has performed in some of the country’s finest concert venues, including Alice Tully, Merkin, and Carnegie Halls. Since obtaining a master’s degree from the Manhattan School of Music, Derek has become a renowned cellist, producer, composer, arranger, conductor, and, ultimately, bass player. His debut album, The Griot Swings the Classics, was released in 2018.

FBPO: How would you describe your musical upbringing?

DM: I’m pretty fortunate that I’m the son of intellectuals, educators, so music was a big part of my childhood. My mom and dad had an incredible – and I mean incredible – collection of albums. I grew up listening to Brook Benton and Sam Cooke, Count Basie, but also Brahms and Beethoven, and Mozart. I grew up in a sort of musically cosmopolitan setting. My dad had been in a glee club when he was in college, and my mom was the organist at the church I went to when I was a youth. Her mother was the pianist. My older brother – I have one sibling – he’s musically inclined, and he can sing, so music was never not a part of my life, Jon.

FBPO: Was the cello your first instrument?

DM: You’re going to love this! I wanted to play bass. I began tinkering on the piano when I was, I guess, between 3 and 4. Then, at the age of 8, I was introduced to string instruments.

FBPO: I’m guessing that was in a school program?

DM: Yes. We saw a demonstration of all the strings, and I was just mesmerized by the low sonorities and the vibes that came off the bass and the cello, mostly the bass. I remember a great blonde bass with nice flames on the side. I was like, “Oh my God! It’s such an amazing instrument!” And I gravitated to it.

FBPO: So how did you end up with the cello?

DM: The guy was like, “Yeah, your hands are really too small. Why don’t you do the cello for right now?” And so that’s how that started. It was a totally unglamorous way to begin. I wanted to play bass, sort of like the Mingus story, but in a different way. And so what happened, Jon, I started rolling with the cello.

FBPO: Even though, deep down, you wanted to play the bass?

DM: I never forgot my first love! I borrowed that teacher’s bass for one summer and I started teaching myself bass solos from Ellington’s “Jack the Bear” and my dad’s Coleman Hawkins albums. The bass has just always been with me. I developed to a concert cellist, so I didn’t really leak it that I was a bass player because it’s difficult when you’re having a career to let people know that you do a little bit of everything. You come across as literally incredible. You come across as people won’t believe it. They’ll think you’re a charlatan. So I kept it under wraps that I was a bass player.

FBPO: I have this image of you in bed when you were a kid with an earphone so you could listen to bass without anybody else knowing it! Is that kind of how it was?

DM: [Laughs] Well, here’s what’s beautiful about it. My childhood was wonderful in that my parents allowed me to explore any artistic means that I found interesting. They didn’t care. I was drawing, I was writing poetry, I was speaking spontaneous rhymes, I was playing music. They bought me a zither, they bought me all sorts of instruments. They didn’t push me, but I had a curiosity about everything artistic anyway. They just sat back and said, “Have at it.”

FBPO: It’s good to hear that your parents were so supportive.

DM: It’s the most beautiful thing a set of parents can do. I’m very fortunate for that. So what happened, my dad already had a bunch of Duke Ellington CDs and Coleman Hawkins CDs, Lionel Hampton… and I would listen to them from my early years, from my single-digit years. We moved to our new house when I was 5. That’s how I can remember. It was right before we moved to the new house where I just fell in love with these sonorities of Lionel Hampton, Basie, Ellington, all this. And something overcame me, where this music became a part of my being. It seeped into my bones and I learned then the only way to really enjoy this music as much as I needed was to play it. It’s not enough to listen to it. It’s not enough to sit back and tap your feet, and hum. I had to play it. And that’s true of me even today. And so I would play the albums, and I’d get the bass and I’d play along with the “Jack the Bear” bass solo and Ellington, over and over again, just to get the feeling of satisfaction of playing that solo until I could play it perfectly.

FBPO: Did you know you were listening to Jimmy Blanton or Percy Heath, or Walter Page, or any of those guys?

DM: No. Absolutely not. No, my mom had lived in Philadelphia for a while and she had gone to a jam session where Slam Stewart was featured.

FBPO: Wow.

DM: Yeah! I’ve known that story for decades now, but I had no idea that bass was important. I only could tell that the music was super sophisticated and sublime. I didn’t know that I was listening to one of the most important composers in the world. I didn’t know that. I just knew that I liked it. And then when I listened to Coleman Hawkins, that’s a whole different head game. That’s a whole different space. But in any event, I was learning these solos, and I had no idea I was putting money in the musical bank for later career stuff, man! And I had no idea.

FBPO: But when you were at the Manhattan School of Music, you were a cello major?

DM: I went to Manhattan School of Music and studied with (Mstislav) Rostropovich’s daughter, Olga (and) got to meet him. Studied with her teacher, Harvey Shapiro, got to hang out, drink liquor, smoke Cubans with him [Laughs].

FBPO: So it wasn’t till you graduated college that you mustered up the courage to “come out of the closet” as a bass player?

DM: That’s a good way (of putting it). I met Yo-Yo Ma, I met Rostropovich, I met Janos Starker. Became friends with Starker and some of these cats. You know, I wanted that life for myself. I wanted to be touring and doing concerti with orchestras, so I couldn’t afford to let out that I also drew and all that stuff ‘cause they’d be like, “There’s no well in hell you could play the Shostakovich concerti if you spend any of your time drawing. You need to be (spending) all your time practicing.” So, I lived that life for a while. I wanted to be the guy who was only the cellist. I wanted to be known as a recitalist. And I made my recital debut playing Paganini and Beethoven and Bach when I was 13, man. I’ve been doing recitals forever! That’s what I wanted for myself.

FBPO: Funny, I’ve never heard Janos Starker referred to as a “cat.”

DM: [Laughs] He liked the fact that I was taking cello in a different direction and used his influence to do it.

Photo by Amy Sexton

FBPO: At what point did you let it be known that you’re also a bass player?

DM: Only recently, quite frankly. Only recently, it opened up a bit. It amplified. I just decided, why hold back any part of who I am? If I do all these different things, and all these different activities bring joy and fulfillment to my life, why in the world would I leave any of them out? It’s time out for that. I lived the life of the sort of, not elitist cellist, but, you know, when you go through grad school, sometimes you’ll walking around with your nose in the air and you start being hypercritical of your colleagues. I lived through all that. That’s for the birds, man. I’ve got thousands of friends all over the world that are amazingly talented, and I just decided it’s time to open up and do what I do. I’ve enjoyed success doing that and I love what I do. People knew I played bass, but I didn’t let it out a lot. It’s only been for the last ten or twelve years.

FBPO: You have a very unique way of expressing yourself musically. How would you describe what you do?

DM: Thank you. That’s… I love it! Because of my disparate interests, which span the bossas of Quincy, well, the bossas of Brazil, but his arrangements, the bop of Mingus, the counterpoint of Beethoven, the neoclassicism of Prokofiev… all of that, Jon, melded in my head in this interesting mélange of expressive options that I have learned, over the years, to call “mruzick” (MROO-zick). It’s my own proprietary thing.

FBPO: Can you explain what it is?

DM: What it boils down to is, you take a Bach air, and we know how amazing Bach was, his perfect placement of notes, or Beethoven, whoever you want to take. What they tapped into, the emotions that those intervals bring from you, are timeless. And so it’s not unusual to find a passage in Bach that you may find in some modern pop group. Or, it’s not unusual to find a passage in Beethoven that you find in the Temptations. And I picked up on that very early in life, such that if I play a Bach air, I add vocal slides and scoops into it as a doo-wop group would do. And you gotta understand, when I was taking lessons under these cats, they were like, “Man, you can’t play music from the 1730s, all Romantically.”

FBPO: It sounds like your teachers didn’t totally embrace the concept.

DM: I knew how to satisfy my teachers, but it was in me to blur the lines between idioms and genres. Because truthfully, what’s the difference between the contrapuntal brilliance of Bach and Mingus with all his lines going? There’s no difference. It’s counterpoint. Either way, it’s counterpoint. It’s the same exact thing. And my mind could not differentiate between the two of them, so what you find me doing now is, I’ll take a hymn, you know, “For All the Saints,” by Ralph Vaughan Williams, and I’ll add major sevenths, and ninths, ala Aaron Copeland. And I’ll slide into certain notes and I won’t vibrate others ala, you know, saxophones and Basie. So all the idioms, Jon, all the genres meet and do a dance together in what I call mruzick. That’s how I express myself.

FBPO: What’s keeping you busy these days? What are you doing with all that disparate stuff?

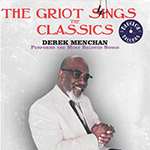

DM: As of yesterday, I just finished recording for my follow-up album to my debut album. My debut album was The Griot Swings the Classics, which performed pretty well. It went twice to the top 3 in the Amazon Contemporary R&B chart. Everything I told you about my upbringing is represented in Griot, meaning some of those vibes I grew up with and some of the very tunes I grew up with end up on the album. I open the album with “One Mint Julep,” the famous Ray Charles/Quincy Jones collaboration, and I knew that from my childhood.

FBPO: And yet you still have a lot more to say?

DM: I’ve got a huuuge, gargantuan follow-up to that. I’m debating whether or not to release it as a double album or whatnot. Something that can be said of album number two, out in September 2020 (title not yet disclosed), is that, as the logical follow-up to my debut album, it is consciously doffing its hat to prominent African American artists of yesteryear, those whom I call “Them Elders.” I’m already working on an exciting third album that takes me in another direction. Album three will go in a new, cosmopolitan direction and will feature some new sounds! I have found that the best way for me to get my thoughts and my ideas out, about music and otherwise, is doing my own thing. I’m a producer, writer, an arranger, and all that, so I’ve found that doing the recording is the way to get my ideas out.

FBPO: Tell me about your gear. I know you play NS Design products, why don’t we start there?

DM: I play a CRM5 and a few months ago I got their flagship, I got their EU 6-string. As far as basses are concerned, I played an NS in a shop twenty-five years ago and I fell in love with the feel and the sound. I said, man, I gotta own one of these bad boys! Now I’ve got two and I’m happy as a pig in you-know-what. I can play regular basses, but with all the high position work I do, I need that body cut out of the way, man. I love sub-sonics! I’m never going to own a 4-string standup. And my first electric will probably be a 6-string, to be honest with you. You dig?

FBPO: What about strings and amps, maybe effects, things like that?

DM: Because I record, I usually go for old fashioneds, Ampeg and stuff like that. A far as strings, Jon, I haven’t jumped into that realm to see what’s going on. I use stuff that’s strung up by NS, and I haven’t had to change them. For electric, I like strings as live and as bright as I can get. I used to like Ernie Ball, but they didn’t last very long. I like bright sounds because they cut through. I do a lot of expressive, very personalized, what we call “rhetorical” work. I sing a lot of things on the bass, and they need to cut through, so the brightness I like. I don’t do effects yet. When I go into my “Parliament” mode and I start visiting that Parliament/Funkadelic sound, I’ll probably get some pedals and effects. I’m a dude who lays down walking bass lines. I’m your pocket man, ya dig? I want it straight and I want it beautiful, and I want it round.

FBPO: Let’s talk about bass technique. What advice can you impart to somebody who wants to learn bass?

DM: I think the most important thing for any artist, and certainly bass players, is that you give yourself enough safe space to fail. Let’s call it exploratory. Let’s call it exploring. Listen to some recordings, see what the bass is doing, let yourself know you can do it, have fun, go to the bass with a smile on your face, open up your ears, train yourself to have big ears, and learn what foundational work is. Get a tune. Hey, man: root-four-five. Lay down that root. Once you can lay down the foundation of a groove, you can become the soloist who uses hammer-ons and harmonics if you’d like. But you don’t have to. The bass world is not necessarily only about flash. Right? We’ve got room for that, but we started out layin’ down bass lines for tight grooves, and without us and the drums, you’re not gettin’ anywhere. [Laughs] So fall in love with what the function of a bass does, get comfortable with that, and then, for Heaven’s sake, the sky is the limit. Pay attention to your left hand, make sure the fingers are always round, make sure they’re not too flat, make them good and strong. Go to a desk, or on your forearm, and go up and down with your fingers to build dexterity and independent movement of the fingers so that when you come to this sometimes-imposing instrument, you have more than what it takes to control the technique. That’s what I would say.

FBPO: What would you be if you weren’t a bass player? And you can’t say a cellist! Something outside of music.

DM: I might be a film director. There’s rhythm in scene changes, there’s rhythm in the lines spoken in a script. I’ve got a few cameras and I dabble with that a bit. If I weren’t able to do music at all, if I weren’t a bass player, I’d probably dabble into cinema. I’d like to do maybe a little bit of acting, I’d do some directing, I believe.

See Jon’s blog, with key takeaways from this interview, here.

Griot Swings the Classics is available here: